In December, the European Union (EU) launched the Global Gateway programme to establish links and promote investments in different parts of the world. The strategy aims to boost clean, innovative, and secure connections in transport, digital energy, and strengthen health, education and research systems worldwide. It also aims to build sustainable links with nations to address contemporary challenges, including climate change, improving health security, and the need to boost global supply chains.

Under the strategy, EU member states hope to mobilise up to $340 billion in investments between 2021 and 2027. European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen called the Global Gateway strategy “a template for how Europe can build more resilient connections with the world” and added that the Union would support smart investments in quality infrastructure, in line with the bloc’s international norms and standards. The initiative is the bloc’s attempt to bridge the global investment gap.

The strategy is also being viewed as an alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) since it aims to counter China’s growing footprint and influence worldwide, especially in Africa and Southeast Asia, where the EU has established itself as a strong player.

The BRI was first launched by China in 2013 by President Xi Jinping to finance projects mainly in energy, telecommunications and transportation sectors across Africa, Asia, and Europe. So far, 138 countries have joined the BRI. According to the report produced by global economic consultants Cebr and sponsored by the CIOB, the BRI is likely to boost the world Gross Domestic Product (GDP) by $7.1 trillion per annum by 2040.

Amongst many ambitious infrastructure projects undertaken under the initiative, the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) worth $60 billion and the China-Europe express railway stand out. So far, China has already spent $200 billion on infrastructure projects as part of the BRI and Morgan Stanley predicts that Chinese investment under the initiative could reach $1.2-$1.3 trillion by 2027.

Under the initiative, China has listed 43 of 55 African countries as partners. In 2018, Chinese investments in Africa stood at $5.4 billion. For instance, China’s mineral investments in Africa alone amounted to $33 billion between 2006 and 2017. On the contrary, the EU is Africa’s leading trading partner, both for exports and imports of goods. In 2018, the total trade between the EU and Africa was worth $266 billion as compared to $141 billion for China. Moreover, during the pandemic, the EU made significant donations of vaccines to Africa and hailed the establishment of local production capacities.

Additionally, the EU’s initiative not only offers solid financial conditions for partners bringing grants, favourable loans, and budgetary guarantees to de-risk investments and improve debt sustainability; but also promotes the highest environmental and management standards. It also highlights how democratic values offer fairness and certainty to investors and offer long-term benefits for people worldwide. On the contrary, China’s BRI has been accused of pushing countries into debt traps. For instance, when Sri Lanka could not repay the loan, the South Asian nation had to hand over a majority stake and a 99-year lease on the Hambantota port to a Chinese firm.

Furthermore, the bloc’s initiative aims to become the modernised version of the BRI by investing in sustainable and future-oriented projects in health, renewable energy, and digital sectors. In contrast, China has mainly invested in infrastructure projects and constructed roads and railroads or renovated ports and bridges and has only recently shifted focus to renewable energy, new technologies, and digital networks.

That being said, the EU’s investment sums make up only a fraction of the money that China has invested and is willing to invest in developing countries since the launch of the initiative. While the total sum available to the EU for investment under the initiative is $340 billion, China has already invested $200 billion as part of its BRI project. Additionally, while the bloc has promised to invest $340 billion over the next five years across the world as part of the global recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic, the majority of the capital consist of existing funds and loans guarantees, which cannot address the infrastructural needs of developing nations.

Moreover, the Global Gateway’s value-based approach makes challenging China’s BRI highly unlikely.

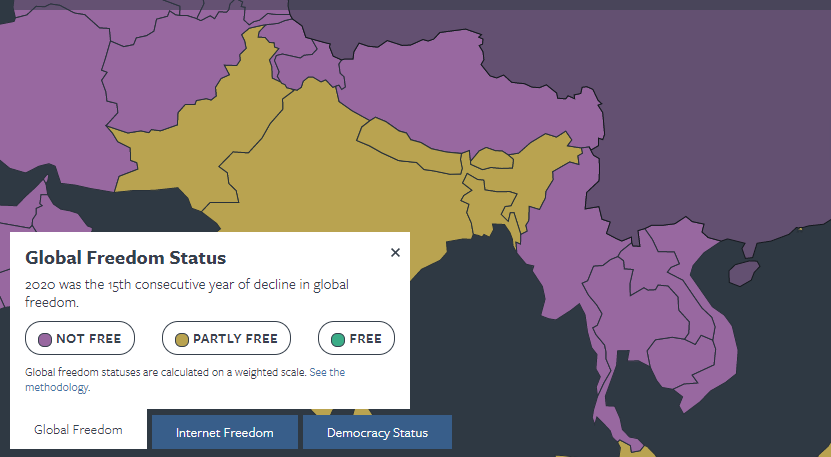

For instance, the EU’s value-based approach conditions the release of funds and investments on transparency and good governance, which many countries in Africa and Southeast Asia might not prefer due to undemocratic regimes. As per Freedom House’s latest rankings on political freedom, out of 11 Southeast nations, only Timor-Leste was classified as “free.” In addition, in the latest Corruption Perceptions Index by Transparency International, Cambodia and Laos were amongst the most corrupt nations.

Given the lack of transparency in governance in these target nations, they tend to prefer Chinese investment over the EU, especially as Chinese loans are not conditioned on democratic ideals. In this respect, Greg Raymond, a researcher at the Australia National University, said, “China is often preferred as a source of infrastructure because Southeast Asian regimes do not want transparency as they are using the Chinese projects as part of patronage politics or lining their own pockets.”

It is also why the BRI is being viewed favourably by a majority of lower and middle-income countries seeking investment, trade opportunities and business, and why they seek cordial relations with China instead of value-driven Western agendas, including respect for the rule of law, human rights, transparency, and good governance.

The EU’s excessive focus on its value-based approach, including good governance and transparency, would deter nations, mainly in Southeast Asia, from applying for investments from Brussels, which would further push them towards the BRI’s ambit despite its debt-trap diplomacy. A senior fellow for Southeast Asia at the Council on Foreign Relations in Washington observed, “The combination of much less funds and that some Southeast Asian countries are going to reject the values aspect of it, will probably not make it [Global Gateway] that successful in Southeast Asia.”

The EU’s investments are limited compared to China. Still, if it collaborates with other countries with similar values-driven approaches, the Union could reduce the infrastructure gap and implement development projects.